THE PUPPET CENTER

FALL/WINTER 2014 ISSUE NO. 36

Table of Contents • Editor's Note • Selections

Chinese puppet theatre from the stage to the museum (and back to the stage)

by Dr. Robin Ruizendaal, director of the Lin Liu-Hsin Puppet Theatre Museum

The museum as a source of inspiration

Traditional Chinese puppet theatre with its rod, string, glove and shadow theatre, is still performed by thousands of professional and amateur companies in the countryside and state companies in the big cities. With the arrival of the era of mass communication in China after the Cultural Revolution in the late 1970s, puppet theatre slowly started to lose its entertainment appeal. Puppets, stages and scripts that survived the Cultural Revolution started to be collected by individuals and institutions and puppet theatre museums and collections are starting to emerge. In this paper we will chart the development of Chinese puppet theatre collections and museums and how these museums can play a role in reviving one of the elaborate puppet theatre cultures in the world, with a focus on the Lin Liu-Hsin Puppet Theatre Museum in Taipei.

The magic and reality of Chinese puppet theatre

In order to understand the magic of Chinese puppet theatre, I will have to take you on a trip, possibly on the back of a truck or on a motorcycle, over winding roads. At dusk we arrive in a village, a stage is erected, there is live music, food, lights, incense burning, prayer and ritual, people gather and then it starts…on the stage the legends, history and gods come alive through the puppets with an elegance that goes right back to the roots of its civilization. The music is loud and beautiful and we are amazed by the colorful spectacle. Food and drinks are offered and we sit down to enjoy the spectacle. What happens next? After some time we realize the less magical element of the performance: it becomes repetitive and we cannot follow the seemingly endless dialogue in the local dialect. We find that the younger generation gathers in a shed nearby to watch Terminator or some other action video. Pensioners continue to watch the puppet show. Young children are mimicking the movements on stage, but do not follow the show. Uneasily we check our watches. The mosquitoes really start to bite now and tomorrow we have to get up early and so we leave for our air-conditioned hotel room, yet with the feeling of having experienced something unique.

Puppet theatre has always been a fascinating window on Chinese society, with its beautifully carved puppets, music, eloquent language and dramatic qualities and its role in numerous religious rituals that accompanied all the major life events of Chinese people. Yet, the era of mass communication has resulted in the disappearance of numerous puppet theatre companies and many companies only perform several times a year. As we mentioned above, the younger generation greatly prefers televised entertainment and for a non-local audience the action is difficult to follow. Nevertheless, there are still several thousand puppet theatre companies in China. The preservation of puppets and this performing art in general has generated substantial government support in China and Taiwan in the past decades. Puppets never die and unlike opera actors remain with us in all their (battered) glory. The collection of Chinese theatre puppets by museums started in the 19th century in the West and now Chinese and Taiwanese museums are catching up rapidly.

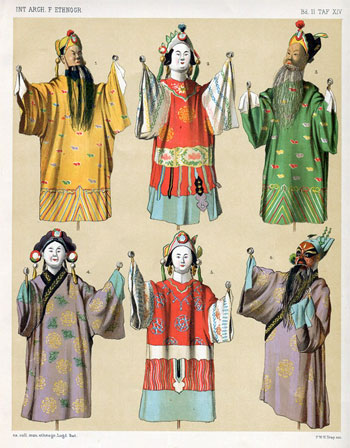

Collecting Chinese puppets by western scholars and artists in the late 19th and early 20th century

After the Opium Wars in the 1840s, China was forced to open up to foreign trade and missionary zeal, but also to scholars of Chinese culture. The first to systematically collect puppets and stages was the Dutch sinologist J.J.M. de Groot (1854-1921) , who did fieldwork in the Amoy (Xiamen) region of Fujian province in the 1880s. He collected complete sets of glove and string puppets from Fujian (including stages) that are now stored at the Ethnographic Museum in Leiden, The Netherlands.

In the 1880s, the interpreter at the Dutch embassy Peking, J. Rhein, wrote one of the first articles on Chinese puppet theatre: "Mededeeling omtrent de Chineesche Poppenkast"[Notes regarding the Chinese Puppet Theatre], which was published in 1889. Rhein was able to buy a set of puppets and a stage. He also described some of the plays that were performed. The puppets are now in the collection of the Ethnographic Museum in Leiden, the Netherlands.

In the 20th century contacts with China and the West intensified and sinologists like Berthold Laufer (1874-1934) collected unique puppets for the Field Museum of Natural History. German collector Karl Eger (1879-1933) collected almost 1500 shadow figures from Sichuan, that found their way in the collection of the ethnographic museum in Munich. Unique individuals like Pauline Benton actively performed shadow theatre, she also collected a substantial collection of shadow figures and brought this art to the U.S., as described in the recently published book by Grant Hayter-Menzies, "Shadow Woman: the extraordinary career of Pauline Benton". All these researchers and other individuals brought these puppets and stages to the West and these puppets are in most cases the most ancient and complete examples of early Chinese puppet theatre.

Professor Jacques Pimpaneau created one of the most unique collections of Chinese and Asian puppets. He inherited the collection of Cantonese rod puppets from the Hong Kong banker Kwok On. He founded the famous Kwok On museum in Paris and managed to extend his collection with numerous unique Chinese glove, rod and string puppets. After the closing down of the museum, collection was in storage for some time, but now has found a home at the Museo do Oriente in Lisboa.

Chinese collectors of puppets

Puppet theatre was the occasionally the subject of paintings and poems in previous centuries. The collection of puppets was never deemed important or at least there is no mention of any puppet collector before 1900 (as far as this author is aware). The first collection of stages and puppet was in Taiwan in the 1930s (at the time a Japanese colony) when the Taiwan Museum acquired the glove puppet stage and puppets of the puppeteer Tong Quan. It was also in the 1930s that a group of Taiwanese alumni of Waseda University in Tokyo donated a beautifully carved puppet stage and glove puppets to the Theatre Museum of Waseda.

After the foundation of the People's Republic of China in 1949, Soviet style cultural politics were implemented. As a result all religious activities were banned and puppet theatre companies were disbanded and puppeteers and musicians concentrated in large government controlled companies. The puppeteers often donated their own collection of puppets and scripts etc. to the company and these companies often had small display rooms. There was a genuine government interest in puppet theatre in the early 1950s and the first history of puppet theatre was published, written by Sun Kaidi. The Shanghai Arts Publishing House published a lavish full colour book on the work of the famous puppet carver Jiang Jiazou.

The state puppet theatre companies now performed outside their own region and even in Peking and abroad with great success. Numerous puppet animation movies of high quality were produced. This period of restructuring and innovation did not last, and with the start of the Great Leap Forward at the end of the 1950s, the focus of the whole country was on rapid industrialization. The failure of the Great Leap Forward led to a power struggle and eventually the Great Cultural Revolution (1966-1976). During the Cultural Revolution all the precious artifacts collected in the state companies and research institutes were destroyed. Puppets, scripts and stages were burned or destroyed, puppeteers were symbols of reactionary forces and mistreated as such.

At the end of the Cultural Revolution, the puppet heritage of China had diminished significantly. Frantic attempts were made to save what could be saved. Puppets hidden under the floors were dug up. People went to the far away countryside to try and find some puppets that were not destroyed. The continued economical development in China in the 1980s and 90s, has also placed a renewed interest in the intangible part of the cultural heritage (while most of China's old cities were destroyed to make place for new construction). Puppet theatre companies started performing again and puppet theatre museums have opened their doors or are now opening up in Quanzhou, Hangzhou and other places, and the huge China Puppet and Shadow Theatre Museum in Chengdu will open in 2014. These museums have managed to salvage part of the heritage and are trying to promote the art of puppet theatre in the age of mass communication. The Lin Liu-Hsin Puppet Theatre in Taipei started experimenting with interactive exhibitions and educational programs in the 1990s, to inspire a new generation, below we share some of the museum's experiences.

The Lin Liu-Hsin Puppet Theatre Museum: an innovative approach to museum exhibitions, promotion and education

The economic boom of Taiwan in the 1980s also led to a renewed interest in its own culture and roots. Puppet theatre always had an important status in Taiwan, because of its many companies (over 300 professional companies), its puppet television station and puppet film industry. Collectors started to move into China to collect puppets on a large scale. Some of these collectors were inspired by puppet museums in the West, such as the former Kwok On museum in Paris of Prof. Jacques Pimpaneau, which had one of the most fantastic collections of Chinese puppets in the world (now in the Museo do Oriente in Lisbon). Paul Lin, a Taiwanese art collector, traveled the world to buy exclusive works of art for his collection. One day, in a museum in Japan, he came face to face with a beautiful 19th century southern Chinese glove puppet; being confronted with the puppet was a moment of awakening for him. Paul Lin decided to focus all his collecting energy on the puppet theatre of Taiwan (and soon including the rest of Asia). The collection grew steadily to almost 10,000 puppet theatre artifacts from all over Asia, with an emphasis on China and Taiwan. Taiyuan Arts and Culture, founded by Paul Lin, attracted a number of specialists to take care of the collection.

In the 1990s, a planning committee started with analyzing the function of a modern puppet theatre museum in an Asian/Chinese cultural context.

We were faced with the following problems:

1. How to promote (traditional) puppet theatre inside Taiwan, where the youth is mainly interested in televised entertainment and their game consoles?

2. How to design exhibitions that inspire the audience to get really involved in puppet theatre?

3. How to preserve over 10.000 puppets made of a wide range of materials?

4. How to promote Asian puppet theatre around the world and preserve its heritage?

Our first action was to create a puppet theatre company that would integrate traditional puppet theatre, as well as find new and innovative ways to present it. The Taiyuan Puppet Theatre Company was founded in 2000, and its members were the old master Chen Xihuang (eighty-three), young puppeteers and modern theatre trained actors and designers. The first two plays that were created—Marco Polo and The Wedding of the Mice—used traditional techniques and puppets, but with modern stage techniques and design. These shows proved to be a great success and, to date, each show has been performed over a hundred times in over thirty countries around the world.

The Taiyuan Company also started an outreach school educational program. In 2000, the Tao-Thiu-Thia Puppet Centre (TTT Puppet Centre) was founded as an experimental puppet center to study what kind of exhibit could inspire visitors. All exhibits in this center were accompanied by a DIY installation where people could operate and play.

Rehearsals and puppet making were all done in the exhibition space. The very interactive nature of the exhibits combined with solid academic research of different puppet traditions resulted in a very successful mini-museum. As a private organization, the centre was able to generate 60% of its income from performances and educational activities, the rest was provided by the government and the Taiyuan Foundation. At the time there were four full-time staff.

In 2005, two buildings in the old part of Taipei were donated to the foundation by Ms. Shi Jinhua to commemorate her husband, the physician Lin Liu-Hsin. The Lin Liu-Hsin Puppet Theatre was founded with a four-story museum, a puppet theatre. Later another office building and storage facility were added. The museum continued with its style of interactive exhibitions and in-depth research. Fieldwork and exchange programs were conducted with most Asian countries and the collection continued to grow. The Taipei City Government Arts Education program stipulates that all second year elementary school students have to visit a puppet museum and see a traditional performance. Over the past few years this has led to huge influx of visitors (and income). The museum focus is not only on the younger generations and the exhibits provide information for all different levels of visitors.

The museum now has the most complete collection of Asian puppet theatre artifacts in the world, with an emphasis on the puppet theatre traditions of Taiwan and China. This resulted in the publication of the book Asian Theatre Puppets by Thames & Hudson in 2009. The collection policy is based on obtaining complete sets of puppets from the different Asian traditions, incl. stages, scripts and instruments, complemented by fieldwork and research.

The conservation department of the museum now consists of two experts, who are responsible for the conservation tasks, as well as the preparations of artifacts for exhibitions. The museum now has two floors of completely climate-controlled spaces for the storage of the different puppets. Continuous study and research is conducted in the best way of preserving the many different materials from which puppets are made. The museum and the puppet theatre company together now have a full-time staff of fourteen and volunteers and interns from around the world. At present, the company performs over 250 shows a year and generates 60-70% of the total revenue. Donations and government support account for 30-40% of the total income. The innovative approach of the museum and theatre company has inspired numerous other companies to follow in its footsteps and create new ways of presenting traditional culture. At present, there are several local and municipal puppet theatre museums and centres in Taiwan, as well as a national elementary and high school puppet competition. In the finals, there are over 120 school companies competing! The Lin Liu-Hsin Puppet Theatre Museum is but a small part of this wonderful tradition, but is continually inspiring people to embrace the art of puppet theatre.