THE ENVIRONMENTAL ISSUES ISSUE

FALL/WINTER ISSUE NO. 52

Table of Contents • Editor's Note • Abstracts

As I sit here looking out the studio window at the fjord on a cold yet sun-soaked day in Hvammstangi, Northwest Iceland, it is easy to let the mind wander. Earlier in the day I took the dog down to the nearby beach to collect driftwood and other less natural debris washed to the shore by the tides. There was a small pod of whales blowing not far from the shore. The dog barked at some seals as they peeked out of the waves, curiosity written in their eyes. I am drawn to the texture of tangled plastic bags that have been stretched and faded by their time in the sea. It feels like a strange new seaweed or mermaid hair. Discarded fishing net created the infrastructure for sand piles and modern housing units for an assortment of sea creatures. The rock crabs are new to these waters. They seem to be thriving. A couple of lads from a nearby village have started a crab fishing business to generate income and control the expanding crab population–adapting to and utilizing the natural resources available to them. In the same village a woman is exploring the different ways seaweed can be used as a sustainable food source in Iceland. She is making dehydrated soup stock. Every day the ocean brings something new to our shores. Sometimes it is lumber from Russia, other times gallon milk jugs from the USA. Often it is more local products–those are the ones that hurt when you see them.

It is easy to paint a picture of Iceland as an environmental utopia. It is recognized as one of the most sustainable countries, using renewable energy sources to provide heat, electricity, hot water, and to power greenhouses. It wasn ́t until the 1970s that Iceland really began to develop as a modern country. Up until that point the United Nations classified Iceland as a developing nation–lacking infrastructure, knowledge about the potential of its resources and still emerging from centuries of poverty and foreign rule. It was not environmental concern that drove the shift to renewables in Iceland–but an economic one, as the country could not afford to import oil.

It also was not large-scale government initiatives that started Iceland’s shift from fossil fuels to renewables. It was rural entrepreneurs. It was a small independent farm holder who first started exploring the use of geothermal energy to power his remote farmstead. This idea was then picked up by small municipalities, and eventually taken up by the national government at which time funding for research and implementation was allocated.

Things tend to start small here. People, especially rural people, are stubborn and independent. You have to be when you are this isolated. It is a difficult and unrelenting lifestyle out here.

The puppetry community in Iceland is small and spread out across the country. We are often isolated and operate on the fringe of society. Our community of professionals is overwhelmingly made up of residents of foreign origin; people who have immigrated here however many months, years, decades ago and decided to practice their art here despite the challenges.

Like the shift to renewable energy resources, Iceland’s shift to sustainable approaches to theatre is being driven not by large institutions, but by individual artists. This is in turn picked up by institutions as artists are given a platform for their work.

As artists our ability to affect change through our practice is very limited. But our ability to create impact through sharing stories, through youth work, through conversation is vast.

OWl PuPPET FROm engi, HaNdbENdi bRúðulEikHús

Last year Helga Arnalds, Artistic Director of 10 Finger Theatre, created a beautiful show at Borgarleikhús (City Theatre in Reykjavik) which used only recycled materials to create the set and costumes. It was a striking visual and a thoughtful and touching story. There has been in general an increase in this kind of theatrical production, certainly throughout Europe, that uses found plastics and upcycled items to create characters, sets, and installations. Bernd Ogrodnik is an advocate for the holistic self- sustainable lifestyle of the artist and use of natural materials, particularly the art of wood carving, which produces the exceptionally designed and crafted puppets we all admire. I applaud these efforts. I think they are worthy and effective when the dramaturgical work supports it. My own company, Handbendi Brúðuleikhús, uses primarily found and natural materials to create sets and puppets. I rarely buy any materials since moving to Northwest Iceland, as I tend to be inspired by the world immediately around me. It is a privilege I enjoy due to my choice to live remotely. It is also a sacrifice. It is not always easy to work in this place. Planning is often your enemy here.

While living the mission is important for our personal motivations and integrity, it is even more important to concentrate on being good at our job–being good storytellers and artists– doing the work that delivers the message. This is where we have impact.

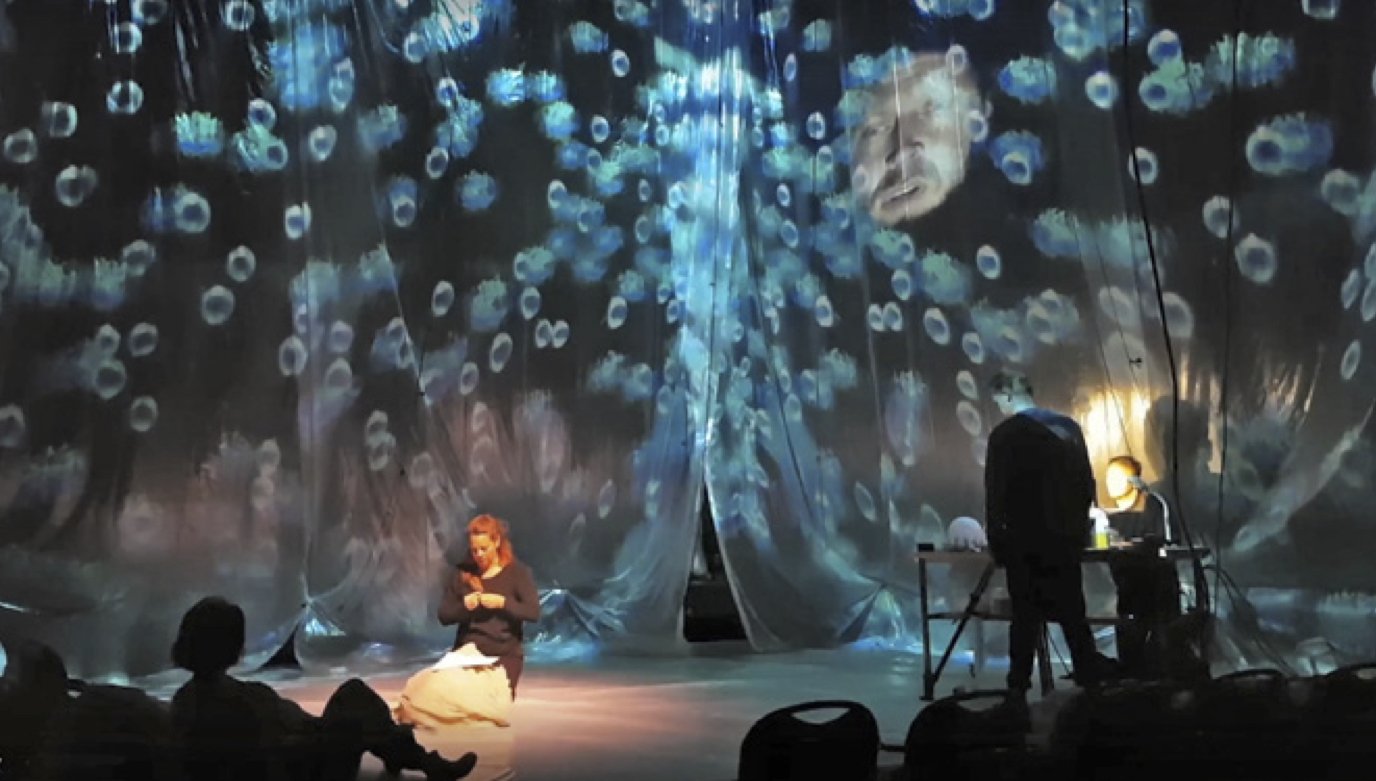

tröll, HaNdbENdi bRúðulEikHús • PHOTO: HElEN muRRay

In December 2020, the town of Seyðisfjörður in the East of Iceland experienced a series of devastating mudslides that swept large sections of the town into the fjord–the result of an unusual amount of rainfall and the thawing of arctic permafrost. The town is protected by barriers, but this time it was different. The thawing of permafrost meant that sections of land previously immune to mudslides were now vulnerable. No one saw it coming. No one was prepared for a mudslide of this scale in that location.

Tess Rivarola, a puppetry artist from Paraguay, had recently moved to the village of 670 people earlier in the year to teach art at the local school. The conversation Tess encountered with her students and local community following the mudslides drove her to question how she could inspire her students and support community healing through arts engagement.

Despite experiencing the impact of climate change in a direct and immediate way, the view of many residents was that, although climate change was a recognized global problem, its effects did not impact their lives “here in Iceland.” The way Iceland has been marketed is at least partially responsible for this perception. If you constantly send out the message that something is flawless, that is what will be believed.

In the same way the USA thinks of itself as the greatest nation on earth despite the evidence to the contrary, Iceland believes in its own image of environmental perfection. And while we are privileged to live in a very clean natural environment, we are not immune to the climate crisis. The arctic is warming at four times the rate of the the rest of the world. The reduction of sea ice, glaciers, and permafrost is rapid and visible as are the changes in weather. And while we joke about how nice it is on the warm days, I struggle to envision myself or my community enduring many more winters like we have had in recent years up here in the north, or to withstand the increasingly powerful wind in what is already considered the third windiest place in the world (the other two being uninhabited). Even the old farmers–the folks who have lived here their entire lives, some of whom remember living in the old turf huts with no electricity to speak of–are saying how difficult it is.

HElga aRNalds: tHe girl wHo Stopped tHe world HTTPs://WWW.TiuFiNguR.is/

So, climate change has been on our minds here. At the last UNIMA World Congress, UNIMA Iceland proposed an Artic & Arctic Periphery Alliance special commission to unite our puppetry communities across this region. The aims of the commission would be to share stories about, for and from the Arctic regions, to research, document and promote indigenous arctic communities, art, and storytelling traditions, and to promote dialogue about climate change and what local people are doing to adapt to rapid environmental changes.

The proposal was met with mixed reactions. Why do we need a special commission for the Arctic region? Can this not be something that the European commission does? Is it necessary for UNIMA to be so active in the discussion about climate change?

The Arctic and Arctic Periphery region is extremely fragile. Just as sea ice is melting and weather is changing, languages and cultures are disappearing with little acknowledgement of what is happening.

What does that feel like, to witness the loss of your culture to circumstances outside of your control–to have your experiences, your world disregarded by larger nations? To be forgotten at the edge of the habitable world? As climate change has an ever-greater impact on the habitability of the world, what are we doing to support and record cultures that will undoubtedly be lost to the need to adapt to global changes (including climate-based migration)?

I have been thinking a lot about what stories I want to tell and how they want to be told–about the people I en- joy working with, the partnerships that bring joy and complicity, and the ones that do the opposite; about materials, how we approach international touring, and how to advocate for change; how to lead by example. I have been thinking about the world my daughter and her friends will be living in and how the gift of creativity and stories will help them adapt to and effect an ever- changing world.

I read an article the other day in the New York Times, which said that Arizona is likely to become the first uninhabitable state in the US with temperatures rising rapidly. According to all reports on climate change recently read, we need to prepare for mass migration. To me this means opening the conversation about cultural diversity and what that means for our small nation. How will Iceland adapt to hundreds of thousands of climate refugees in the coming decades? How will the conversation change? What cultural remnants will survive the changes to come?

Stories of the effects of climate change–personal authorial stories–are more frequently rural, as the impacts are possibly more evident to those who make their living from the land itself. This is why it is vital that we support rural-based artists. Share the story of the woman who has lived in the same house in the same village for ninety years and watched her region thrive and struggle in equal measure. Tell the story of the child who listens to the breathing of the earth as she explores the world in isolation. Showcase the artist who works in the least accessible corners of the world so their experience can be heard. These voices matter to our understanding of the world as it is, has been, and will be.

These are the kinds of stories the UNIMA Arctic Alliance is interested in promoting. Stories of, or related to, the lives and experiences of people and animals who call the arctic home. Through stories we can increase awareness and empathy: We connect. And that is how we can affect dialogue and change.

Sharing every step of success, no matter how small, is influential. The public participates in a transition that they understand and want. In Iceland, the municipalities that had gained steady access to geothermal hot water became powerful role models for others to do the same. It is my sincere belief that as artists we can be a powerful voice for change when we work together and shout about our successes, share the work our compatriots are doing, get the word out, and let it be known that we are here. That we see. That we hear. And that we feel. That our stories matter.

Heimferd memory Box 1: HaNdbENdi bRuðulEikHus

I told you it is easy to let the mind wander here. I’m about to take the dog out again. The wind has picked up, but he is insistent that we get down to the sea one more time today. The fjord will look completely different in this weather than it did earlier. Everything is so changeable. In our lifetime, this little village might grow, become huge even. The ocean currents could change–taking the seals and the whales with them as they did the herring and the shrimp before. The glaciers will melt. It is hard for us to envision and believe in such fundamental changes. But we must. In order to survive. And we, the artists of the world, need to be open to teaching others to imagine such big, earth-shattering concepts. Through stories. That is my vision of sustainability.

GRETA CLOUGH is an international award winning Amercian puppeteer and theater director based in Hvammstangi, northwest Iceland. She is the Artistic Director of Handbendi Brúðuleikhús and the Hvammstangi International Puppetry Festival, former Associate Artist at Little Angel Theatre, London, and the president of UNIMA Iceland.